Introduction to Ethnic Studies

Author(s): Gregory Yee Mark , Boatamo Mosupyoe , Brian Baker , Julie Figueroa

Edition: 3

Copyright: 2011

Pages: 494

Edition: 4

Copyright: 2022

Pages: 380

Edition: 4

Copyright: 2022

Pages: 380

Choose Your Format

Choose Your Platform | Help Me Choose

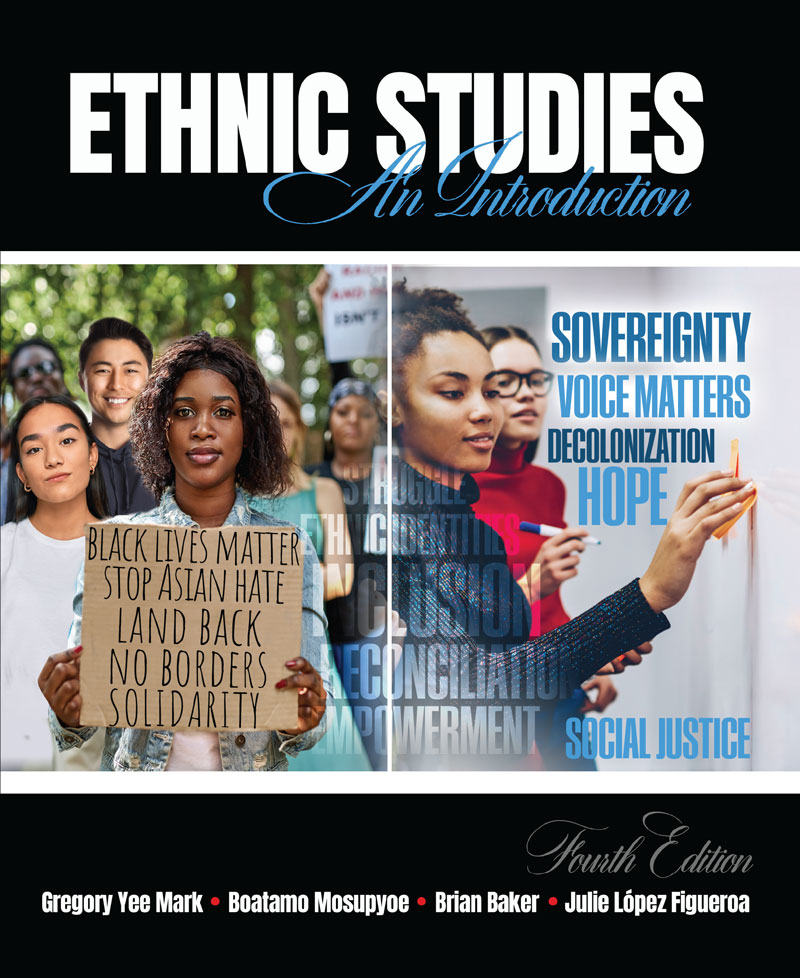

The new 4th Edition of ETHNIC STUDIES: An Introduction reflects the interdisciplinary nature of Ethnic Studies - the readings are drawn from academic fields in the humanities and social sciences. A few first-person narratives are also included, so we can get a sense of how individuals experience their ethnic group status. Overall, the readings in this book are meant to provide students with a foundation in Ethnic Studies.

The volume integrates framing and reflection questions throughout to foster critical and engaged readers. These questions initiate a personal and classroom dialogue.

Respecting the unique realities confronting the communities discussed in this volume, the authors intentionally aimed to evoke a sense of empathy and solidarity so that when students read the words like Black Lives Matter, Stop Asian Hate, Land Back, and No Borders listed, and capped off with the word

Solidarity, these terms would reassert the humanity and dignity of someone else’s lived experiences.

Introduction / Perspectives

Dedication

Introduction to Ethnic Studies

Brian Baker and Julie López Figueroa

“We’re Going Out. Are You With Us?” The Origins of Asian American Studies

Gregory Yee Mark

Why Ethnic Studies Was Meant for Me

Rosana Chavez, M.S. (Ethnic Studies Alumna)

“Ethnic Studies Embodies Activism”

Andrea L. Moore

Framing the Value and Purpose of Perspectives

Julie López Figueroa

History

Introduction

Wayne Maeda (in memoriam) and Brian Baker

“Returning Home Tolowa Dee-ni”

Annette L. Reed, Ph.D.

The History of Asians in America

Timothy Fong

Recent African Immigration

Boatamo Mosupyoe

Native Americans and the United States, 1830–2000 Action and Response

Steven J. Crum

Iu Mien—We the People

Fahm Saelee

The Hmong in the United States

Bao Lo

Race, Class and Gender

Introduction

Boatamo Mosupyoe

The Intersection of Race, Class and Gender

Boatamo Mosupyoe

What It Means to Be an Asian Indian Woman

Y. Lakshmi Malroutu

Is the Glass Ceiling Cracked Yet? Women in Rwanda, South Africa and the United States, 1994–2010 183

Boatamo Mosupyoe

Tungtong: Share Your Stories

Marietess Masulit

Fiji and Fijians in Sacramento

Mitieli Rokolacadamu Gonemaituba, Neha Chand, Darsha Naidu, Jenisha Lal, Jonathan Singh, Shayal Sharma, and Gregory Yee Mark

Identity and Institutions

Introduction

Brian Baker

Kill the Indian, Save the Child: Cultural Genocide and the Boarding School

Debra K. S. Barker

My Father’s Labor: An Unknown, but Valued History

Julie López Figueroa and Macedonio Figueroa

“Imaginary Indians” Are Not Real

Brian Baker

Implicit Bias: Individual and Systemic Racism

Rita Cameron Wedding

“And it’s time for them to come down”: History, Memory, and Decentering Settler Colonialism

Rose Soza War Soldier

Response and Responsibility

Introduction

Eric Vega and Julie López Figueroa

Challenging the Dilemma of Brown v. Topeka Board of Education: And the Rush Toward Resegregation

Otis L. Scott

A Voyage of Discovery: Sacramento and the Politics of Ordinary Black People

David Covin

Arizona: Ground Zero for the War on Immigrants and Latinos(as)

Elvia Ramirez

Asian American and Pacific Islanders Harmed by Trump COVID-19 Blame Campaign

Timothy P. Fong, PhD

“We can’t just stand aside now”: Oakland’s Fortune Cookie Factory Stands with Black Lives Matter

Annalise Harlow

The 65th Street Corridor Community Collaborative Project: A Lesson in Community Service

Gregory Yee Mark, Julie López Figueroa, Christopher Shimizu, Jasmine Duong, and Jazmine Sanchez

Gregory Yee Mark is a Professor Emeritus of Ethnic Studies at Sacramento State University. In January 1969, as an undergraduate student at the University of California (UC) Berkeley, he was a member of the Third World Liberation Front that went On Strike at the Berkeley cam[1]pus to create the discipline of Ethnic Studies. During this transformative student strike, he was tear-gassed, shot at by the police, and most importantly, he learned the true meaning of creating a relevant education for all people. He is a pioneer in the field of Asian American Studies. As an undergraduate student, Dr. Mark was a community organizer and activist in Berkeley and Oakland. He has continued this role as a community advocate and educator while as a professor at San Jose, Honolulu, and Sacramento.

Born in South Africa Boatamo Ati Mosupyoe is a Professor of Ethnic Studies/Pan African Studies and Associate Dean at California State University, Sacramento. She obtained her Bachelor’s degree at University of the North in South Africa and her Masters and PhD. at University of California, Berkeley. Her research is intersectional and includes Gender, Education, Religion, Social and Transitional Justice, and Immigration. She is the Vice President of Global Majority an organization that conducts training and education on implicit bias, conflict resolution and peace building. She was a member of the California State University Task Force on the Advancement of Ethnic Studies, and co-authored the final report. The recommendation of the report effectively served as a foundation for the AB 1460 Bill that culminated in a law mandating Ethnic Studies as a requirement. Dr. Mosupyoe has organized successful International Conferences on the prevention of Genocide and is a recipient of many awards.

Brian Baker is a Professor of Ethnic Studies and serves as the Director of Native American Studies at Sacramento State. With an emphasis on systemic discrimination, settler colonialism and decolonization, he been in researching and presenting on historical and contemporary imagery associated to Native Americans, and how images of “the Americana Indian” have framed the experiences Native peoples within American society. In addition to advising and mentoring students of color he is especially active in working with Native American students. He is committed to community service and engagement which is key to the Ethnic Studies discipline. A first-generation college student, Brian completed his B.S. degree in Sociology, Political Science and Native American Studies at Northland College, eventually completing a Ph.D. in Sociology at Stanford University. He is a citizen of the Bad River (Mashkiiziibii) Band of Lake Superior (Kitchi-gami) Chippewa (Anishinaabe).

Julie López Figueroa is a Professor of Ethnic Studies at Sacramento State University. With a focus on retention, her qualitative research focuses on access and success of first-generation students within higher education, specifically Latino males. She is nationally recognized as one of the earliest contributors informing and framing the body of knowledge examining the academic success of Latino males in higher education. In terms of making college accessible for underrepresented communities, Julie has served as the Faculty Fieldtrip Coordinator for the 65th Street Corridor Community Collaborative Project for the last 17 years. Julie completed her doctoral studies in Education from the University of California, Berkeley; a M.A. in Education from the University of California, Santa Cruz; and her B.A. in Sociology and Chicano Studies from the University of California, Davis. She's the proud daughter of Mexican migrant parents, Macedonio and Maria Figueroa.

Why History Matters to Me

Julie López Figueroa, Ph. D.

Professor of Ethnic Studies

As the daughter of two Mexican migrant parents (Macedonio and Maria) , story telling was so central to my life growing up. While I was too young to grasp the meaning of the story telling, I so enjoyed listening to my parents individually and together share their lived experiences. The way they strung words together caused me to laugh, cry, or feel inspired. As a first-generation college student preparing to move away to college, living away from my family was not going to be easy. Reflecting on the lived histories my parents shared—about why and how they immigrated to the United States, my Dad’s contribution as a Bracero during World War II, my Mom’s courage to be the President of PTA at my elementary school with support of an interpreter, how they were migrant farmworkers that transitioned to cannery work to provide stability for their children—led me to realize that going to college would directly honor my parents’ legacy of courage. Contending with a reality of being poor, not speaking English, and not having a formal education—as was the case for my parents—there is a level of vulnerability that could easily transform into fear. But, their lived histories were showing me how to live, really live with purpose not fear.

Harnessing the courage, inspiration, and strength led me to graduate from the University of California, Davis with a double major in Chicana and Chicano Studies and Sociology, then evolved to completing an M.A. degree in Education from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and finally led me to obtain a Ph.D. in Social and Cultural Studies in Education from the University of California, Berkeley. While I am grateful for the numerous mentors and friends, that I met along the way to show me how to academically succeed at each stage of my academic career, the emotional strength and tenacity that moved me forward as a first-generation student was nourished entirely by my parents lived histories.

As a Professor in Ethnic Studies, this discipline serves as one doorway to historical revisionism, while at the same time recovers dignity and humanity of the communities we study. History is not just about the past, but rather constantly being created through the ways we make sense of and respond to the world around us. Toggling between the past and the present generously positions us to make a choice to either appreciate what we have lived through or take for granted what has transpired. As someone who strongly believes that history manifests ideologies though action, I think it is extremely important to bridge the lives of my students to not only the broader events in history but invite them to make an intimate connection through their lived experiences. To this point, I invite all of us to imagine a world where we can dare to appreciate, and dare to value history that may not be our own, but if we listen carefully we have the opportunity to gain a deeper sense of ourselves in relationship to each other.

The new 4th Edition of ETHNIC STUDIES: An Introduction reflects the interdisciplinary nature of Ethnic Studies - the readings are drawn from academic fields in the humanities and social sciences. A few first-person narratives are also included, so we can get a sense of how individuals experience their ethnic group status. Overall, the readings in this book are meant to provide students with a foundation in Ethnic Studies.

The volume integrates framing and reflection questions throughout to foster critical and engaged readers. These questions initiate a personal and classroom dialogue.

Respecting the unique realities confronting the communities discussed in this volume, the authors intentionally aimed to evoke a sense of empathy and solidarity so that when students read the words like Black Lives Matter, Stop Asian Hate, Land Back, and No Borders listed, and capped off with the word

Solidarity, these terms would reassert the humanity and dignity of someone else’s lived experiences.

Introduction / Perspectives

Dedication

Introduction to Ethnic Studies

Brian Baker and Julie López Figueroa

“We’re Going Out. Are You With Us?” The Origins of Asian American Studies

Gregory Yee Mark

Why Ethnic Studies Was Meant for Me

Rosana Chavez, M.S. (Ethnic Studies Alumna)

“Ethnic Studies Embodies Activism”

Andrea L. Moore

Framing the Value and Purpose of Perspectives

Julie López Figueroa

History

Introduction

Wayne Maeda (in memoriam) and Brian Baker

“Returning Home Tolowa Dee-ni”

Annette L. Reed, Ph.D.

The History of Asians in America

Timothy Fong

Recent African Immigration

Boatamo Mosupyoe

Native Americans and the United States, 1830–2000 Action and Response

Steven J. Crum

Iu Mien—We the People

Fahm Saelee

The Hmong in the United States

Bao Lo

Race, Class and Gender

Introduction

Boatamo Mosupyoe

The Intersection of Race, Class and Gender

Boatamo Mosupyoe

What It Means to Be an Asian Indian Woman

Y. Lakshmi Malroutu

Is the Glass Ceiling Cracked Yet? Women in Rwanda, South Africa and the United States, 1994–2010 183

Boatamo Mosupyoe

Tungtong: Share Your Stories

Marietess Masulit

Fiji and Fijians in Sacramento

Mitieli Rokolacadamu Gonemaituba, Neha Chand, Darsha Naidu, Jenisha Lal, Jonathan Singh, Shayal Sharma, and Gregory Yee Mark

Identity and Institutions

Introduction

Brian Baker

Kill the Indian, Save the Child: Cultural Genocide and the Boarding School

Debra K. S. Barker

My Father’s Labor: An Unknown, but Valued History

Julie López Figueroa and Macedonio Figueroa

“Imaginary Indians” Are Not Real

Brian Baker

Implicit Bias: Individual and Systemic Racism

Rita Cameron Wedding

“And it’s time for them to come down”: History, Memory, and Decentering Settler Colonialism

Rose Soza War Soldier

Response and Responsibility

Introduction

Eric Vega and Julie López Figueroa

Challenging the Dilemma of Brown v. Topeka Board of Education: And the Rush Toward Resegregation

Otis L. Scott

A Voyage of Discovery: Sacramento and the Politics of Ordinary Black People

David Covin

Arizona: Ground Zero for the War on Immigrants and Latinos(as)

Elvia Ramirez

Asian American and Pacific Islanders Harmed by Trump COVID-19 Blame Campaign

Timothy P. Fong, PhD

“We can’t just stand aside now”: Oakland’s Fortune Cookie Factory Stands with Black Lives Matter

Annalise Harlow

The 65th Street Corridor Community Collaborative Project: A Lesson in Community Service

Gregory Yee Mark, Julie López Figueroa, Christopher Shimizu, Jasmine Duong, and Jazmine Sanchez

Gregory Yee Mark is a Professor Emeritus of Ethnic Studies at Sacramento State University. In January 1969, as an undergraduate student at the University of California (UC) Berkeley, he was a member of the Third World Liberation Front that went On Strike at the Berkeley cam[1]pus to create the discipline of Ethnic Studies. During this transformative student strike, he was tear-gassed, shot at by the police, and most importantly, he learned the true meaning of creating a relevant education for all people. He is a pioneer in the field of Asian American Studies. As an undergraduate student, Dr. Mark was a community organizer and activist in Berkeley and Oakland. He has continued this role as a community advocate and educator while as a professor at San Jose, Honolulu, and Sacramento.

Born in South Africa Boatamo Ati Mosupyoe is a Professor of Ethnic Studies/Pan African Studies and Associate Dean at California State University, Sacramento. She obtained her Bachelor’s degree at University of the North in South Africa and her Masters and PhD. at University of California, Berkeley. Her research is intersectional and includes Gender, Education, Religion, Social and Transitional Justice, and Immigration. She is the Vice President of Global Majority an organization that conducts training and education on implicit bias, conflict resolution and peace building. She was a member of the California State University Task Force on the Advancement of Ethnic Studies, and co-authored the final report. The recommendation of the report effectively served as a foundation for the AB 1460 Bill that culminated in a law mandating Ethnic Studies as a requirement. Dr. Mosupyoe has organized successful International Conferences on the prevention of Genocide and is a recipient of many awards.

Brian Baker is a Professor of Ethnic Studies and serves as the Director of Native American Studies at Sacramento State. With an emphasis on systemic discrimination, settler colonialism and decolonization, he been in researching and presenting on historical and contemporary imagery associated to Native Americans, and how images of “the Americana Indian” have framed the experiences Native peoples within American society. In addition to advising and mentoring students of color he is especially active in working with Native American students. He is committed to community service and engagement which is key to the Ethnic Studies discipline. A first-generation college student, Brian completed his B.S. degree in Sociology, Political Science and Native American Studies at Northland College, eventually completing a Ph.D. in Sociology at Stanford University. He is a citizen of the Bad River (Mashkiiziibii) Band of Lake Superior (Kitchi-gami) Chippewa (Anishinaabe).

Julie López Figueroa is a Professor of Ethnic Studies at Sacramento State University. With a focus on retention, her qualitative research focuses on access and success of first-generation students within higher education, specifically Latino males. She is nationally recognized as one of the earliest contributors informing and framing the body of knowledge examining the academic success of Latino males in higher education. In terms of making college accessible for underrepresented communities, Julie has served as the Faculty Fieldtrip Coordinator for the 65th Street Corridor Community Collaborative Project for the last 17 years. Julie completed her doctoral studies in Education from the University of California, Berkeley; a M.A. in Education from the University of California, Santa Cruz; and her B.A. in Sociology and Chicano Studies from the University of California, Davis. She's the proud daughter of Mexican migrant parents, Macedonio and Maria Figueroa.

Why History Matters to Me

Julie López Figueroa, Ph. D.

Professor of Ethnic Studies

As the daughter of two Mexican migrant parents (Macedonio and Maria) , story telling was so central to my life growing up. While I was too young to grasp the meaning of the story telling, I so enjoyed listening to my parents individually and together share their lived experiences. The way they strung words together caused me to laugh, cry, or feel inspired. As a first-generation college student preparing to move away to college, living away from my family was not going to be easy. Reflecting on the lived histories my parents shared—about why and how they immigrated to the United States, my Dad’s contribution as a Bracero during World War II, my Mom’s courage to be the President of PTA at my elementary school with support of an interpreter, how they were migrant farmworkers that transitioned to cannery work to provide stability for their children—led me to realize that going to college would directly honor my parents’ legacy of courage. Contending with a reality of being poor, not speaking English, and not having a formal education—as was the case for my parents—there is a level of vulnerability that could easily transform into fear. But, their lived histories were showing me how to live, really live with purpose not fear.

Harnessing the courage, inspiration, and strength led me to graduate from the University of California, Davis with a double major in Chicana and Chicano Studies and Sociology, then evolved to completing an M.A. degree in Education from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and finally led me to obtain a Ph.D. in Social and Cultural Studies in Education from the University of California, Berkeley. While I am grateful for the numerous mentors and friends, that I met along the way to show me how to academically succeed at each stage of my academic career, the emotional strength and tenacity that moved me forward as a first-generation student was nourished entirely by my parents lived histories.

As a Professor in Ethnic Studies, this discipline serves as one doorway to historical revisionism, while at the same time recovers dignity and humanity of the communities we study. History is not just about the past, but rather constantly being created through the ways we make sense of and respond to the world around us. Toggling between the past and the present generously positions us to make a choice to either appreciate what we have lived through or take for granted what has transpired. As someone who strongly believes that history manifests ideologies though action, I think it is extremely important to bridge the lives of my students to not only the broader events in history but invite them to make an intimate connection through their lived experiences. To this point, I invite all of us to imagine a world where we can dare to appreciate, and dare to value history that may not be our own, but if we listen carefully we have the opportunity to gain a deeper sense of ourselves in relationship to each other.